David Dawson, David and Eli in progress, 2004

The relationship between master and apprentice is evident in the works from painter Lucian Freud and his assistant David Dawson now on view at Faurschou Beijing through August 14th. Dawson has worked as Freud’s assistant since 1991 and has been one of the few people allowed to photograph Freud in his studio as he works. The exhibitions pairs Freud’s painting David & Eli, (2003-04) with ten photos taken by Dawson at Freud’s studio between 2004 to 2006.

Installation view of Lucian Freud and David Dawson at Faurschou Beijing

More text and images after the jump…

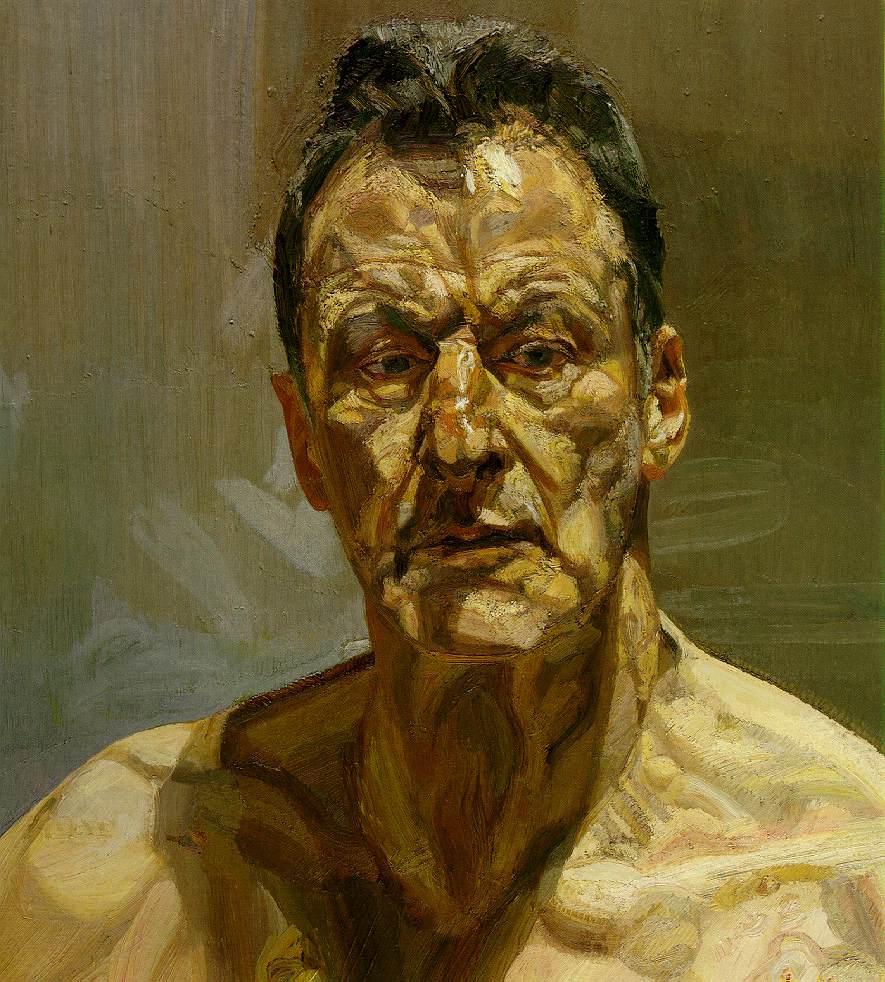

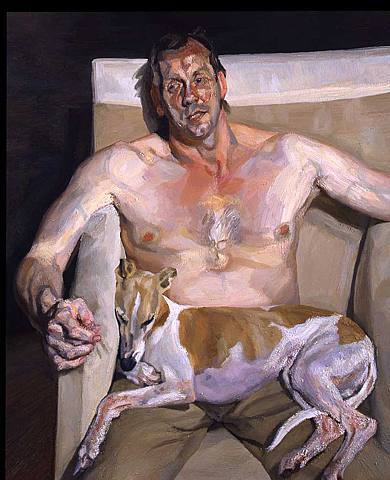

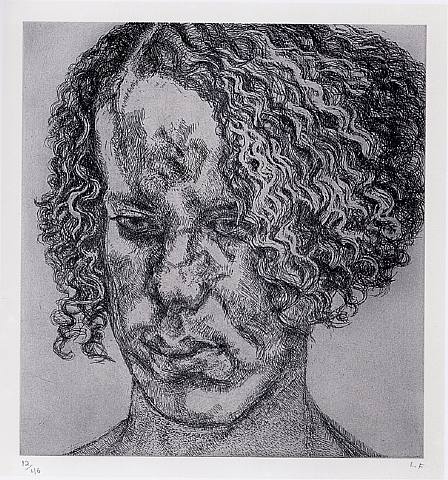

Lucian Freud, David & Eli, (2003-04), all images via Faurschou Beijing

Freud’s painting David & Eli acts as the working point for the entire exhibition. Dawson posed as the model for the figure, and Freud has rendered him in his usual style—a reclining nude in a minimal setting with few distractions. Freud is meticulous in his handling of features and expressions, and his models have been known to sit for long periods of time as he works. Many of his models are friends and fellow painters with whom he has developed close personal relationships, allowing him move beyond simply painting a portrait of the subject, instead evoking a specific personality.

David Dawson, Falling Over

David Dawson, Working at Night, 2005

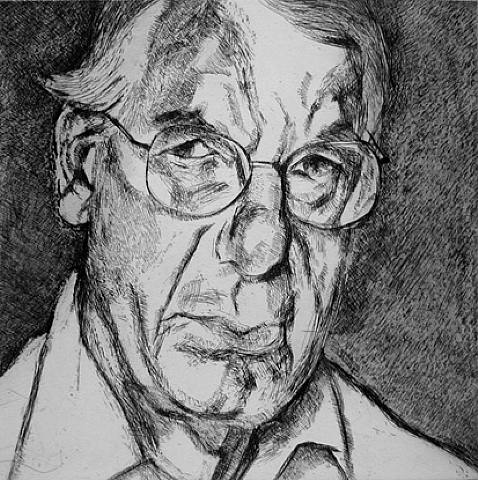

Dawson’s photographs of Freud’s studio space and of Freud himself feel like a private survey into a close partnership. In Working at Night (2005), Dawson captures Freud as he works in what could be seen as a vulnerable state—shirtless with his brushes and palette, about to return to a painting— yet the artist is clearly at ease with Dawson’s camera.

David Dawson, Naked Admirer

David Dawson, Lucian with fox cub (2005)

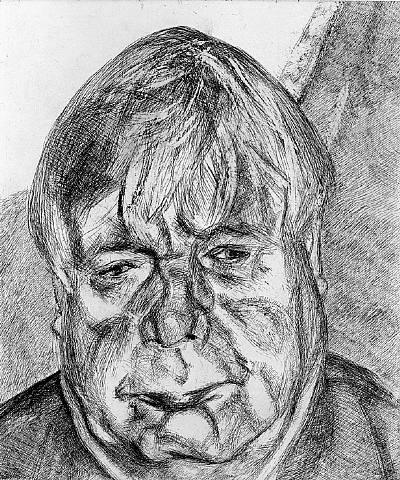

In another photograph, an unfinished version of David & Eli rests in Freud’s studio. We not only see the work, but also the process behind it- we are allowed to witness the mass of paint collected on the walls and recognize the plant and basket that appear in David & Eli. We see the studio as both a working environment and a place of privacy, and how, after having spent 20 years together, Freud and Dawson have developed a professional relationship that allows for reflection on their creative process.

Lucian Freud died recently on Wednesday, July 20th at the age of 88 at his home in London.

Installation view of Lucian Freud and David Dawson at Faurschou Beijing

Installation view of Lucian Freud and David Dawson at Faurschou Beijing

- C. Hughes-Greenberg

Related Links:

Exhibition Page [Faurschou Beijing]Life with Lucian [Guardian]

Art_prospect

The relationship between master and apprentice is evident in the works from painter Lucian Freud and his assistant David Dawson now on view at Faurschou Beijing through August 14th. Dawson has worked as Freud’s assistant since 1991 and has been one of the few people allowed to photograph Freud in his studio as he works. The exhibitions pairs Freud’s painting David & Eli, (2003-04) with ten photos taken by Dawson at Freud’s studio between 2004 to 2006.

Installation view of Lucian Freud and David Dawson at Faurschou Beijing

More text and images after the jump…

Lucian Freud, David & Eli, (2003-04), all images via Faurschou Beijing

Freud’s painting David & Eli acts as the working point for the entire exhibition. Dawson posed as the model for the figure, and Freud has rendered him in his usual style—a reclining nude in a minimal setting with few distractions. Freud is meticulous in his handling of features and expressions, and his models have been known to sit for long periods of time as he works. Many of his models are friends and fellow painters with whom he has developed close personal relationships, allowing him move beyond simply painting a portrait of the subject, instead evoking a specific personality.

David Dawson, Falling Over

David Dawson, Working at Night, 2005

Dawson’s photographs of Freud’s studio space and of Freud himself feel like a private survey into a close partnership. In Working at Night (2005), Dawson captures Freud as he works in what could be seen as a vulnerable state—shirtless with his brushes and palette, about to return to a painting— yet the artist is clearly at ease with Dawson’s camera.

David Dawson, Naked Admirer

David Dawson, Lucian with fox cub (2005)

In another photograph, an unfinished version of David & Eli rests in Freud’s studio. We not only see the work, but also the process behind it- we are allowed to witness the mass of paint collected on the walls and recognize the plant and basket that appear in David & Eli. We see the studio as both a working environment and a place of privacy, and how, after having spent 20 years together, Freud and Dawson have developed a professional relationship that allows for reflection on their creative process.

Lucian Freud died recently on Wednesday, July 20th at the age of 88 at his home in London.

Installation view of Lucian Freud and David Dawson at Faurschou Beijing

Installation view of Lucian Freud and David Dawson at Faurschou Beijing

- C. Hughes-Greenberg

Related Links:

Exhibition Page [Faurschou Beijing]Life with Lucian [Guardian]

Art_prospect