Without words

Ann Jones – Art and Writing

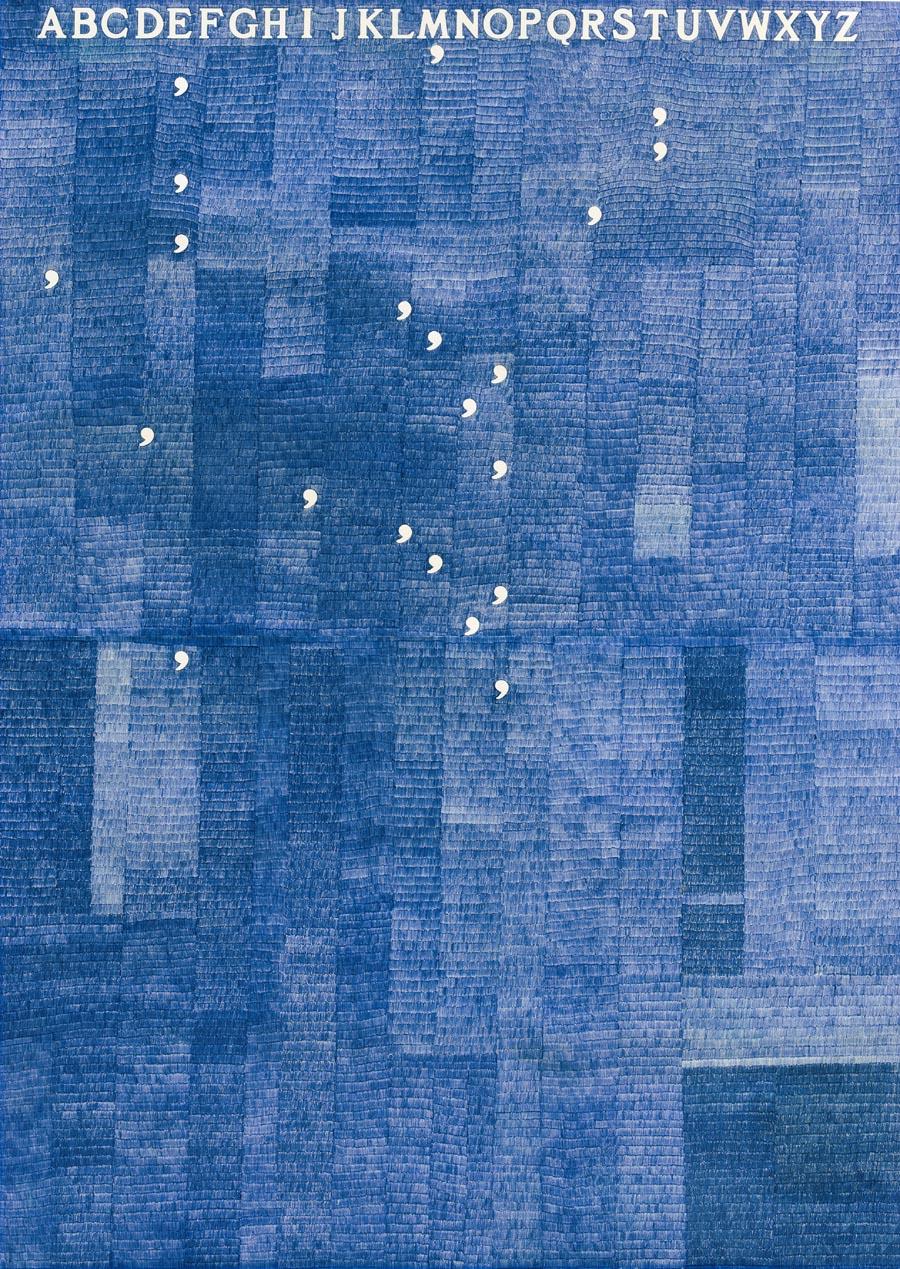

Alighiero Boetti, Mettere Al Mondo Il Mondo (Bringing the World into the World), 1975

Alighiero Boetti, Mettere Al Mondo Il Mondo (Bringing the World into the World), 1975There are three paying exhibitions at Tate Modern at the moment. The Damien Hirst exhibition is being widely advertised and has been the subject of a lot of media attention. Of the other two, the Yayoi Kusama seems to have generated the most discussion. Hirst is of course a household name and Kusama was already firmly in the consciousness of Londoners with an interest in contemporary art following Walking in my Mind at the Hayward Gallery in 2009 which was heavily centred on her work, indeed her polka dot wrapping of the trees along the South Bank ensured that her work also reached a signifcant non-art audience. The Hirst and Kusama exhibitions are also the ones making the most – visual – noise in the gallery, and while the Hirst was proved mercifully quieter than I had expected when I visited, they do seem to be attracting the bigger crowds.

There were things I liked about the Hirst – it was good to see those early works again and entertaining to stare in horror at the worst excesses of his more recent output – and I really liked the Kusama exhibition (at some stage I may well write about both) but it’s the other show – Alighiero Boetti: Game Plan – that I found by far the most inspiring.

Mettere Al Mondo Il Mondo (detail)

Mettere Al Mondo Il Mondo (detail)In the late 1960s, Boetti was part of the Arte Povera movement in Italy, making art from unexpectedly ordinary – poor – materials. Though Tate Modern staged a major exhibition of Arte Povera work from the 1960s and early 70s in 2001, and usually includes work by these artists in its collection displays, and though other Arte Povera artists have been the subject of notable exhibitions in London in the last few years (such as Michelangelo Pistoletto at the Serpentine and Pino Pascali at Camden Arts Centre, both in 2011), this is the first real survey of Boetti’s work here. And it’s quietly fascinating.

Boetti is can’t just be defined as an Arte Povera artist though – he rejected the definition in the early 1970s – so that although Game Plan opens with work that is seen as falling within that movement, the show also is primarily based around his later work which defies such categorisation. The work is interesting in many ways and for many reasons and as usual I’m not going to attempt to do more than write about a couple of works. There was a lot here to like though so there’s every reason to suspect I’ll come back to Boetti again; the maps in particular seem likely to work their way in here at some point and I reckon Boetti may creep into a post about artists using other people to make the work. For today though I’s all about Boetti and the biro. And commas, I especially liked the commas.

Boetti made a number of works using biro inclusing a series of large scale drawings – for want of a better description – based around text and called Mettere Al Mondo Il Mondo (or Bringing the World into the World) which include the alphabet at the top or side of the work with a mass of scrawl. The only legible symbols are the commas, white space cut into the sea of blue biro, which punctuate the space and, in conjunction with the letters at the side or top of the page, allow the work to be decoded and become the text of the title.

The scale of these pieces is part of what makes them work so well for me – I’m not sure I’ve come across other examples of biro drawings on this scale, but they’re to be encouraged in my book – but the real fascination is in Boetti’s use of pattern and code, something that recurs throughout the exhibition. There is something mesmerising about these works that comes in the main from the intensity and repetitious nature of the marks and the negative space of the commas that punctuate the space.

Aerei, 1989

Aerei, 1989Elsewhere in the exhibition there are other works that have much in common with the biro text pieces – there are key approaches that Boetti used repeatedly – including other large scale biro pieces such as Aerei (orAirplanes), and biro sky wildly overcrowded with planes of many types.

Boetti’s work uses systems, patterns and codes in a way that is absorbing and at times funny. The work is highly conceptual but though the hand of the artist is generally absent nonetheless the work has real warmth. This is a show that gave me a lot to think about. This is work that speaks quietly but it’s well worth listening to.

Thanks to: http://imageobjecttext.com/2012/05/09/without-words/